MISSISSIPPI FLOODS

DESIGNING A SHIFTING LANDSCAPE

Mississippi Floods calls attention to the role of visual representation in turning the Lower Mississippi into a ‘landscape of flood’ with levees, revetments, pumps, and gates that work to hold a river to a course within two lines. It documents and constructs the lower Mississippi landscape through places defined by measures of flood, but also places of cultural richness and material depth that do not always conform to lines drawn.

The Mississippi floods despite heroic efforts to confine its course. These floods recur—as they did more recently in 1993, 1995, 1998, and 2005—with billions of dollars in measurable destruction and immeasurable distress. They are a concern not only for the American heartland but also for the many nations that aspire to the flood control measures employed by the Mississippi. The Mississippi after all nourishes and drains 41 percent of the world’s most powerful—and wealthy—nation. Yet the war that it has declared on the Mississippi is far from won or, for that matter, lost. It has merely become an everyday practice, embodying conflict in a unique landscape of levees, cuffoffs, revetments, overflow channels, floodways, locks, gates, and jetties.

This landscape of conflict, the result of efforts to prevent floods while exploiting the Mississippi’s unrivaled navigation potential and, importantly today, valuing its ecological role, is itself the subject of much dispute. The sense of permanence, security, and prosperity that designed interventions have promised is being questioned in Congress and by individuals in academia and the popular press, much more so after Hurricane Katrina. While some continue to believe that the Mississippi can be harnessed and controlled, others advocate that it be released into some natural state. Proponents of these views, and of many others, take their positions with regard to a landscape already constructed, its horizons defined. Meanwhile little attention is paid to the representations that play a significant role in constructing the Mississippi that is the subject of these views.

These representations include maps, hydrographs, cross sections, working drawings, and models used by professionals in the process of designing this landscape, but also, in a more popular vein, photographs, media reports, paintings, and folklore that have contributed to the reception and inhabitation of this designed landscape. These representations reveal a shared idea of the Mississippi, no matter how diverse the views, a Mississippi already captured by a larger public imagination before the war on the ground is fought. They hold the promise of a discourse not merely on the divisive views of the Mississippi but on the imaginative content of its construction.

In 1996 we began a journey across the Lower Mississippi. It took us through documents—maps, surveys, engineering drawings, newspaper reports, books—as well as a varied material terrain—sites with rich and layered phenomena and the focus of repeated surveys and conflict. The recounting of this journey constructs this panorama of a working landscape. It attempts to bring into public discourse the images instrumental in the design of the Lower Mississippi, thereby broadening appreciation for the life of a wondrous landscape.

The panorama begins at the Mississippi Basin Model, a working model of a river located near the town of Clinton, Mississippi. Built in the 1940s by the Army Corps of Engineers, the model marks a culmination of an era of maps and surveys, and a starting point in the design of significant control structures on the Mississippi. We call this cumulative point of departure Site 0. From here we travel four terrains, each a focus of repeated surveys and conflicts, each a force in its own right in the construction of the Mississippi Landscape, each elusive. They are meanders, flows, banks, and beds. We call them Sites 1, 2, 3, and 4.

The elusiveness of these terrains has not stopped the Corps from pursuing their definition. The efforts of the Corps have resulted in interventions that match the Mississippi in magnificence. These interventions have an impact not only on the river but on larger lands of the Mississippi's making. They also bring life to these lands, forcing them into the inexhaustible gray zone between people and river that marks the Lower Mississippi.

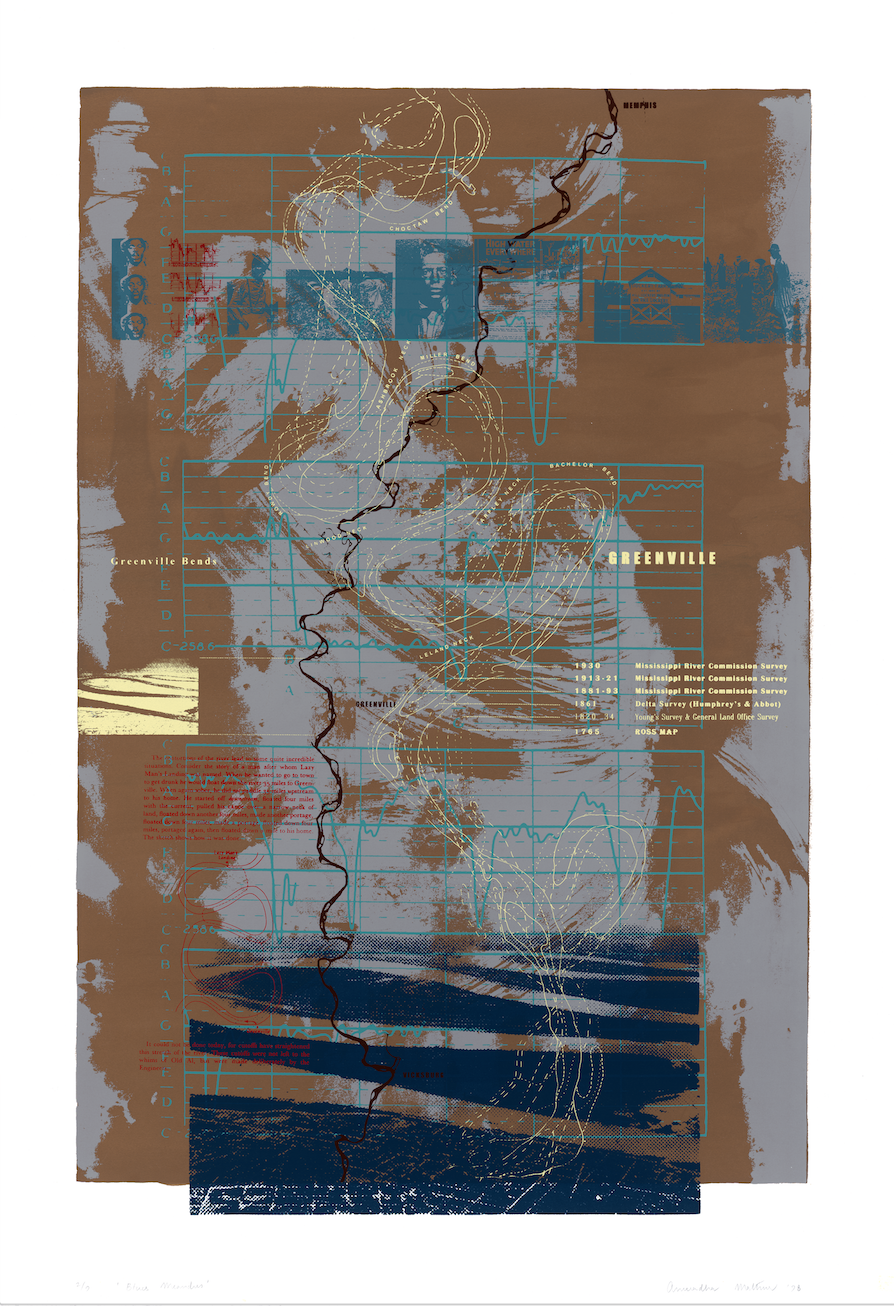

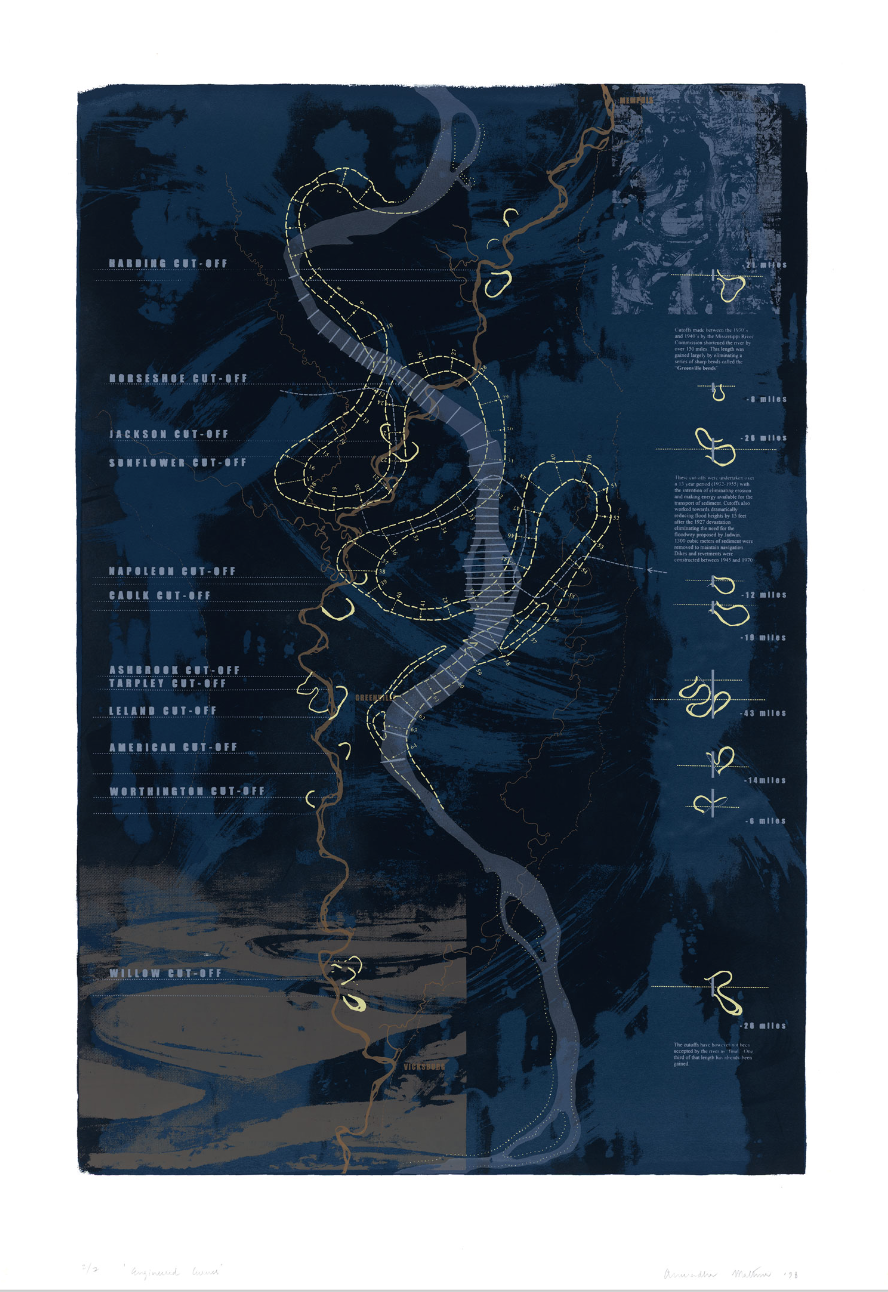

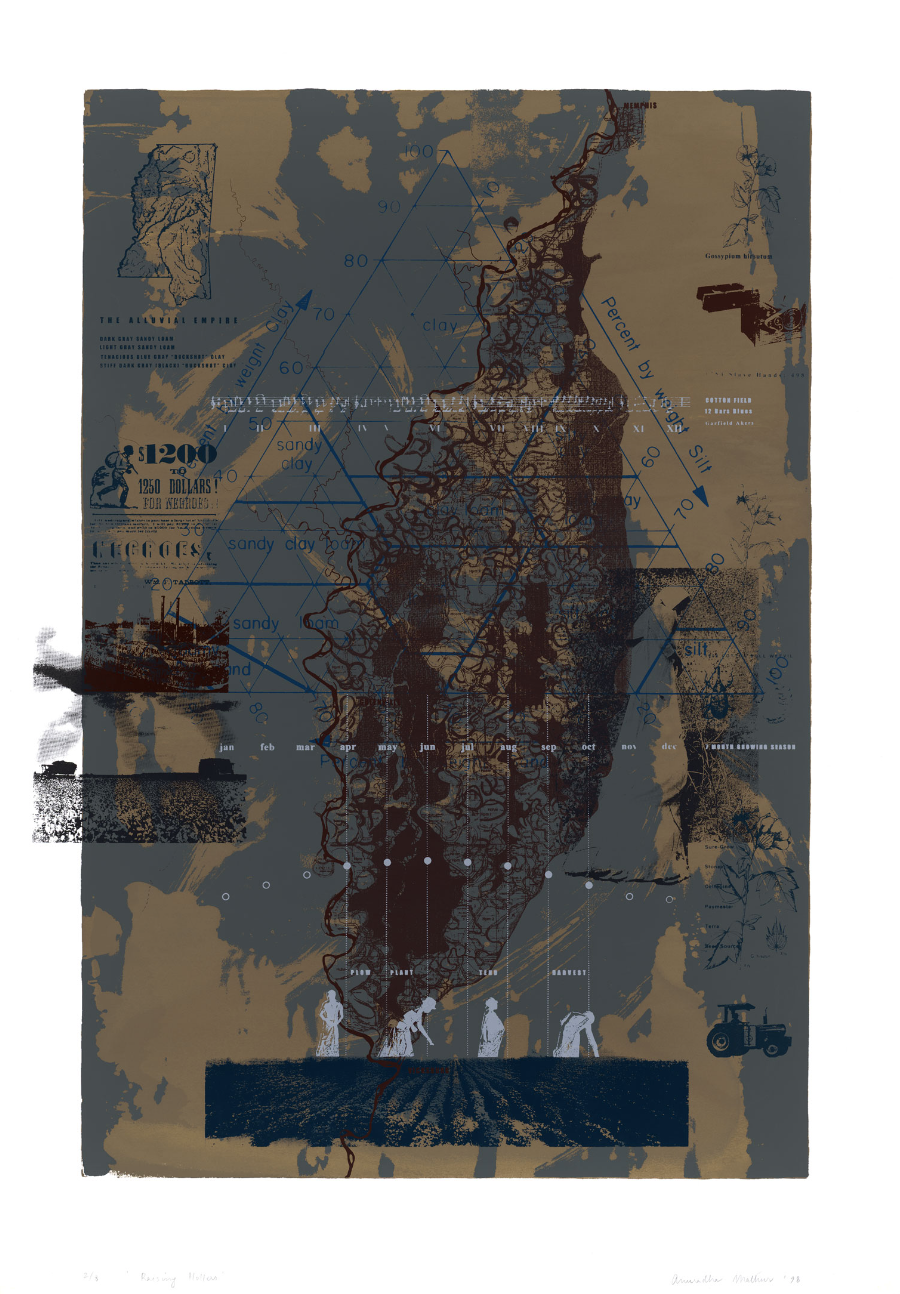

SITE 1 MEANDERS

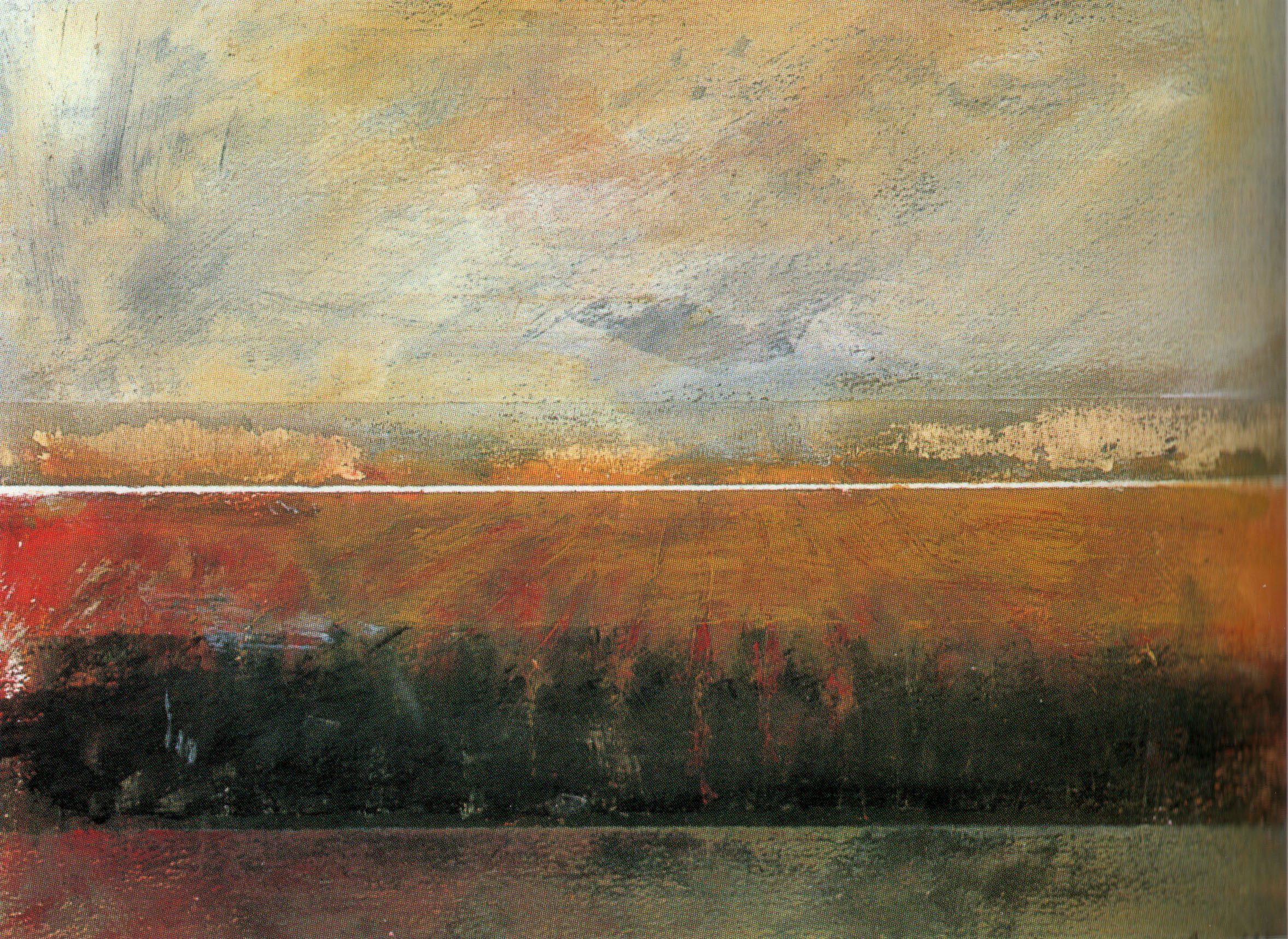

We were led to Site 1 through the engineered cutoffs of the Greenville bends. In the process of straightening the Mississippi, the Corps cut through many such bends stilling the meandering power of the Mississippi. It is a power with which the Mississippi has laid the soil of the entire valley. Nowhere is this imprint more clearly portrayed in satellite pictures than in the neighboring Yazoo Delta. The delta opened a world not only of former courses of the Mississippi, but also of the resistance and rhythms of the Delta Blues, a music with roots in the hollers of slaves who worked the cotton fields and built the railroads and levees. Noted for its elusiveness, blues is the voice of this landscape cleared and drained for plantations. In the delta the engineered curves of the Corps reside uneasily with the meanders of the blues.

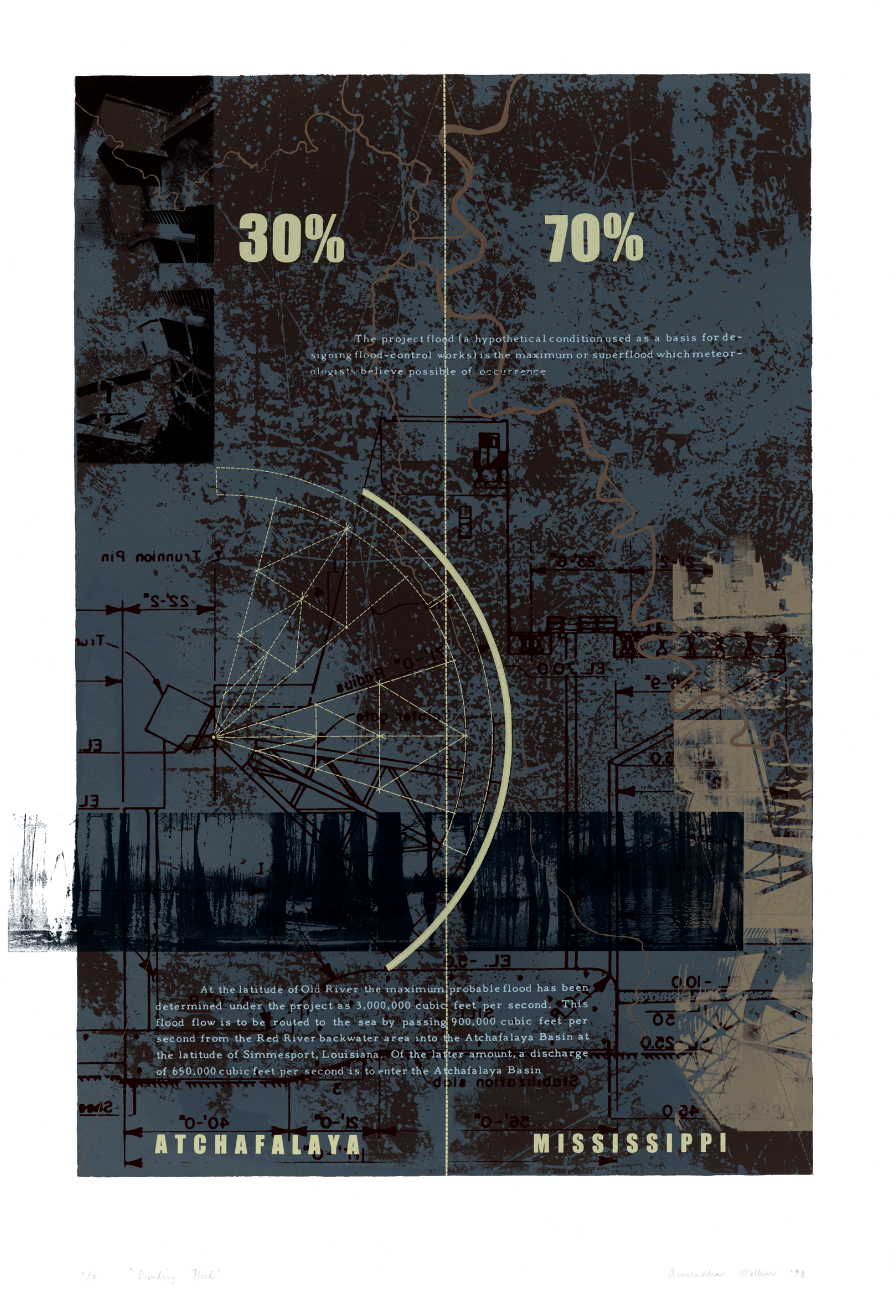

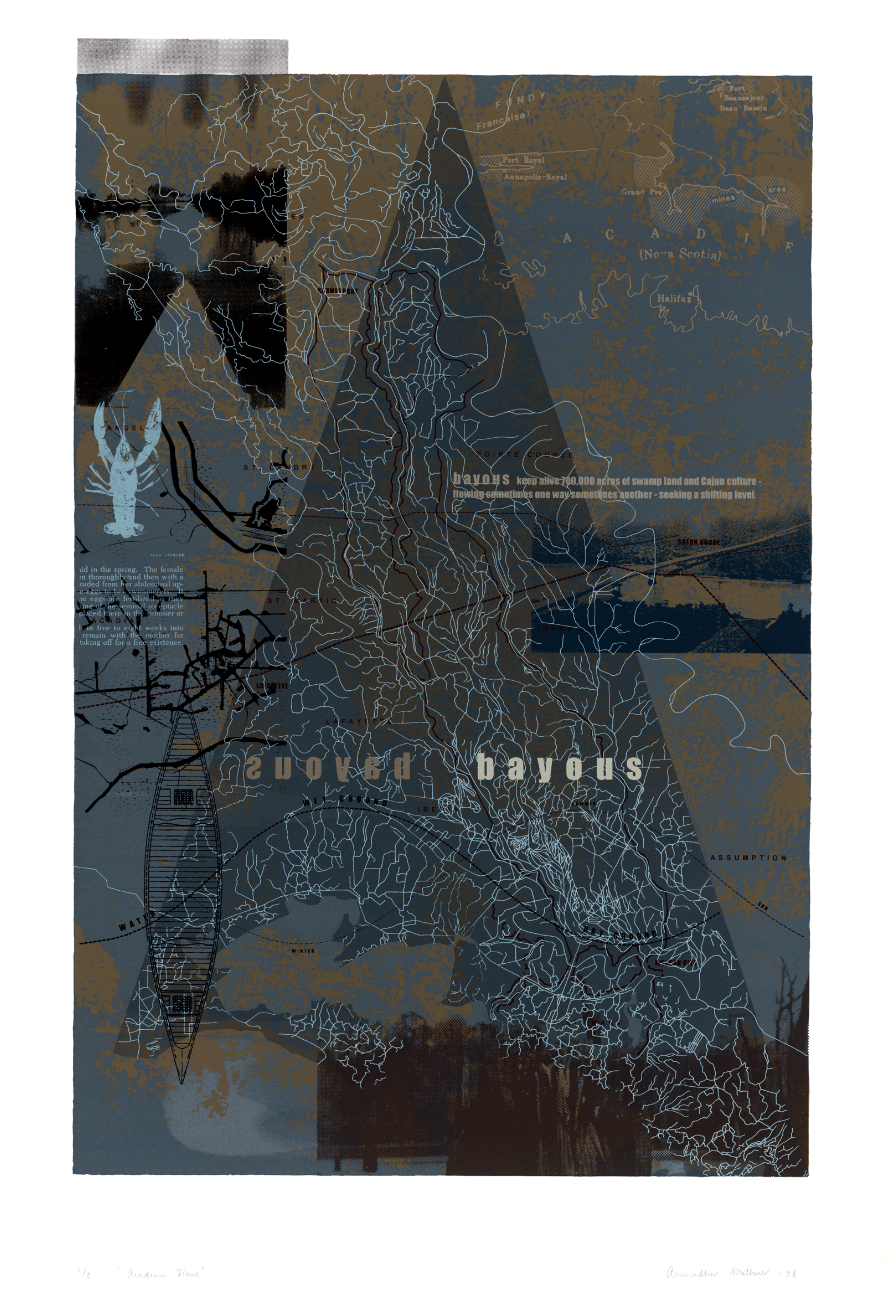

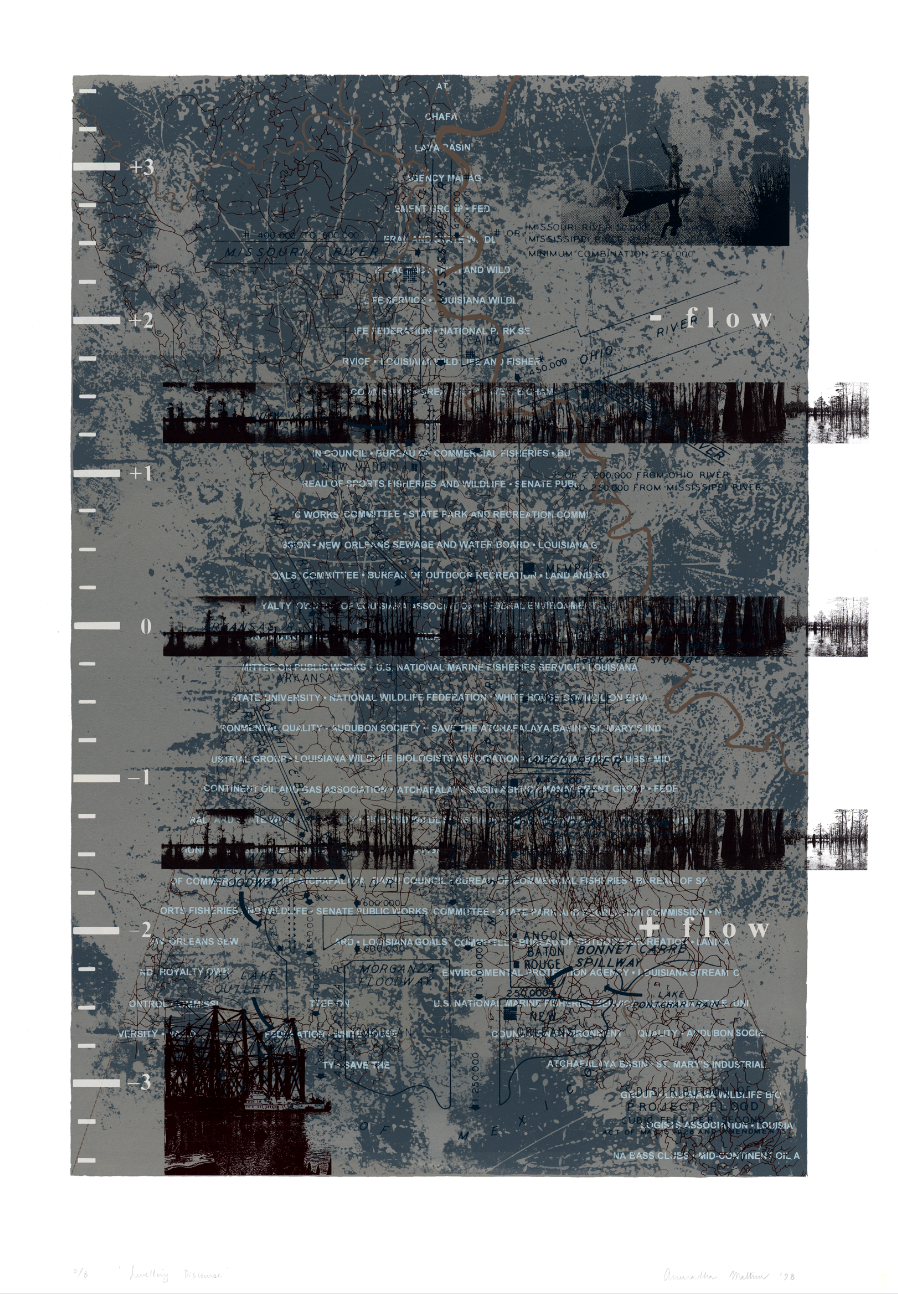

SITE 2 FLOWS

Site 2 was opened to us by the controversial accounts of the control structures at Simmesport, Louisiana, a place popularized by John McPhee in Control of Nature as the most direct confrontation between the Mississippi River and the U.S. Government. Here the Mississippi for decades has been suspected of wanting to change its course. In an effort to keep the Atchafalaya River from capturing the Mississippi the Corps has inherited the flow of eight hundred thousand acres of labyrinthian bayous and swamps of the Atchafalaya basin. This living breathing terrain is home not only to the bayous that are famous for defying any rules of movement, and the subtle resistance of the Cajuns who live off them, but also the multiplicity of conflicting interests, each desiring a different flow.

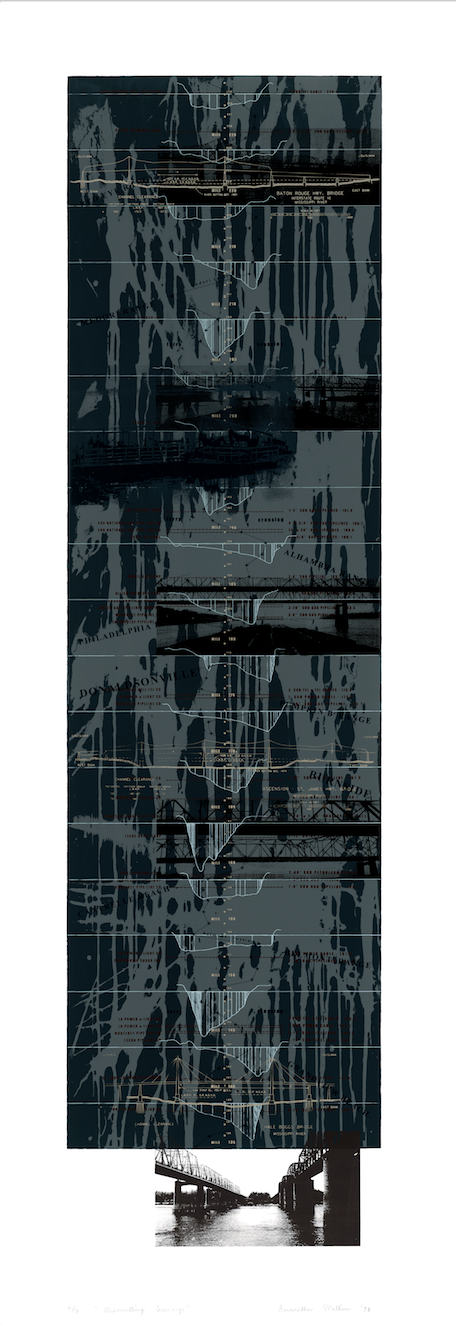

SITE 3 BANKS

Site 3 originated with the levees that appeared in maps and accounts in the early eighteenth century and steadily extended to define a river corridor. Although these feats of engineering today line almost the entire length of the Lower Mississippi, they are most prominent both on the ground and in politics along the corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. Here more than anywhere else, they channel the river, hastening silt and sediments to the Gulf. Levees keep the Mississippi from overflowing, a crossing of water that raised and enriched its banks with the deposition of land that has so contentiously been cultivated first by a plantation culture and today by a booming petrochemical and transportation industry. The antebellum homes, oak alleys, shacks, and sugarcane fields reside uneasily along this corridor with around the clock rhythms of a global corporate industry.

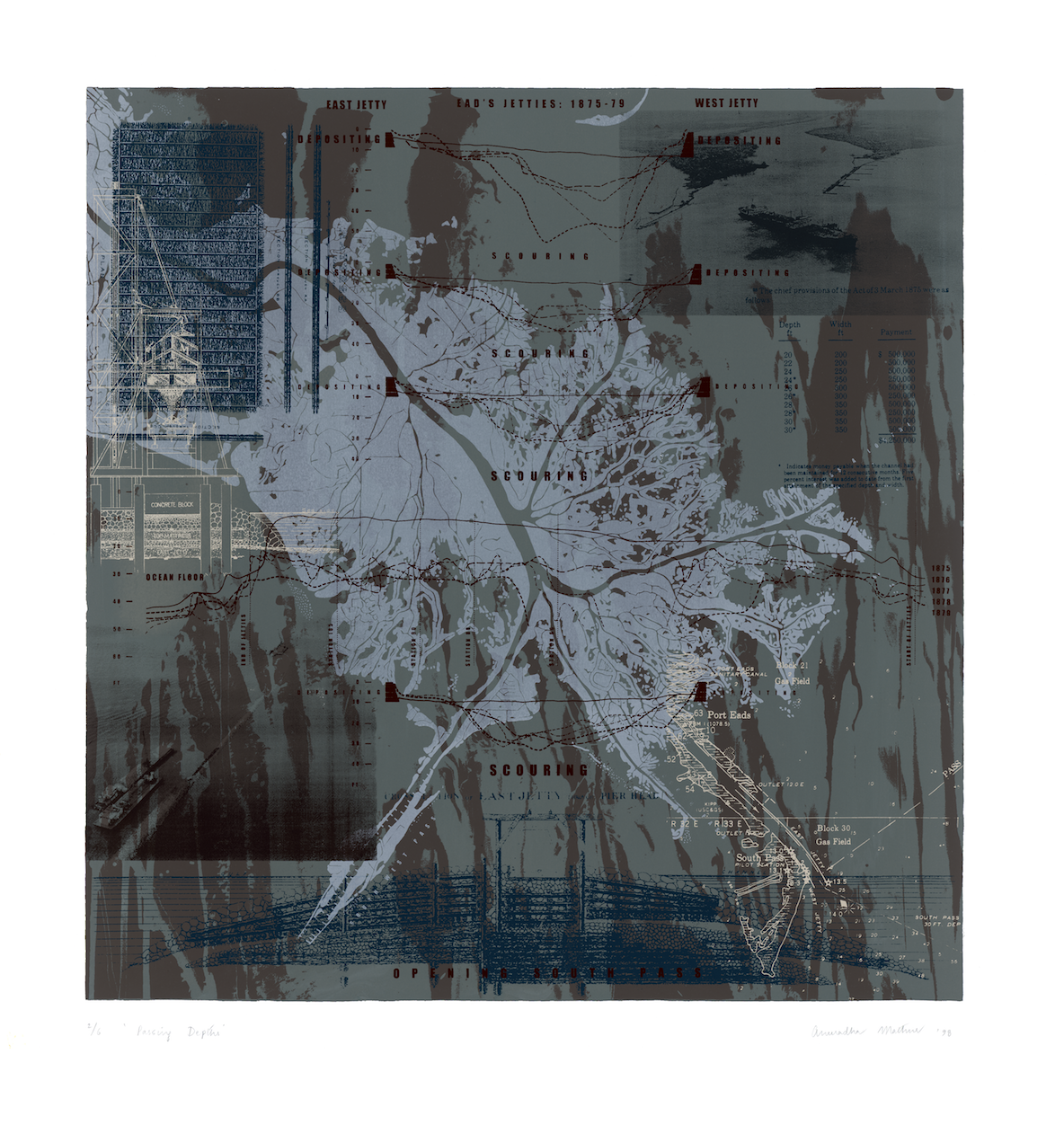

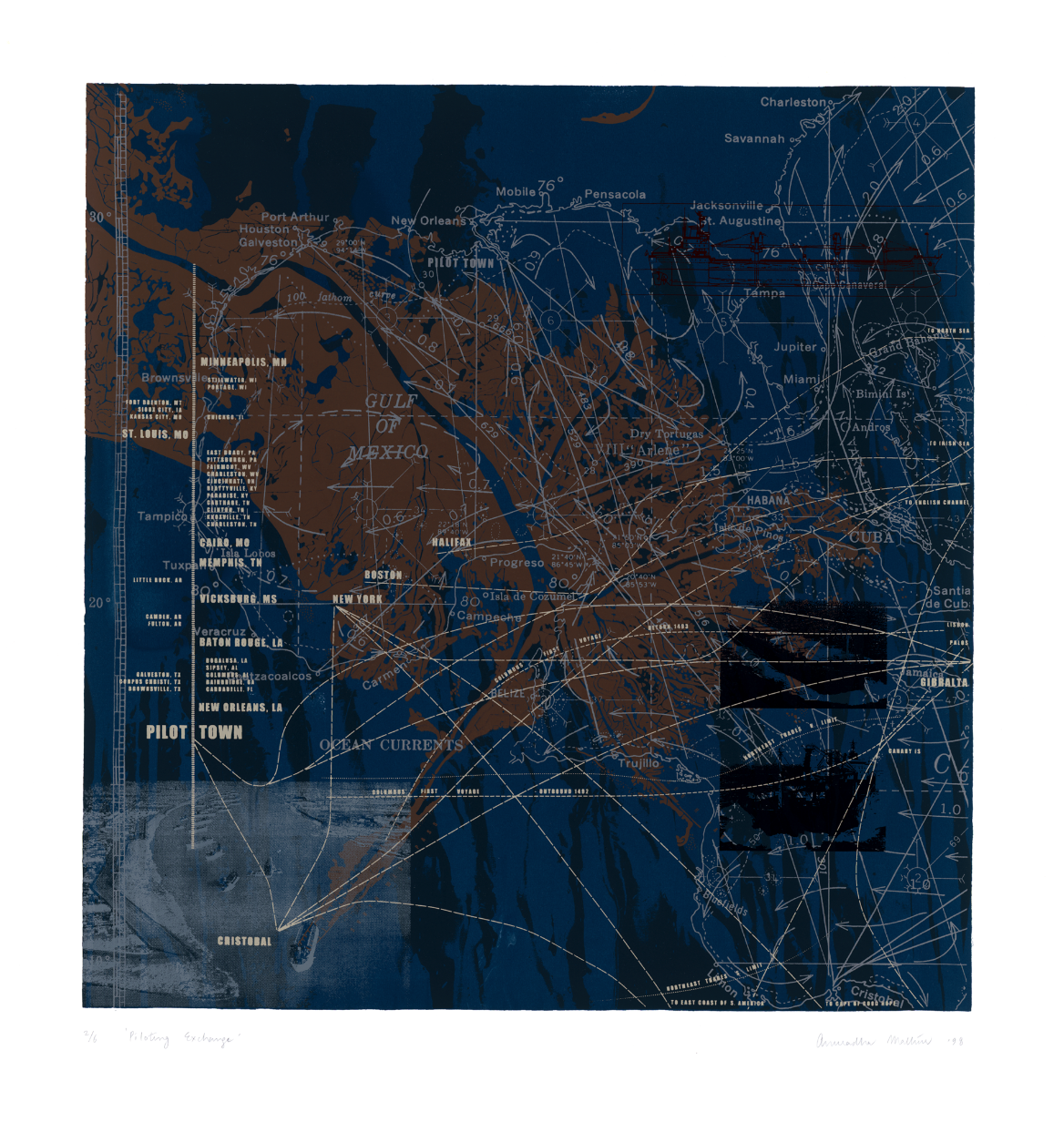

SITE 4 BEDS

We entered Site 4 through the legendary design conflict over the opening of the passes at the mouth of the Mississippi, one hundred miles below New Orleans. The battle between the civil engineer James Eads, designer of the first steel bridge at St. Louis, and the Corps is well documented. It was a fight over the choice between strategic constructions of jetties to urge a Mississippi laden with sediment of a continent to dredge its own bed and the daily dredging of the passes sanctioned by the Corps. Eads won the battle in the late 1800s and opened the continent to dependable trade. Pilottown is the most recent of a number of amphibious settlements that facilitate the exchange between ocean and river pilots. Here, on the threshold of its release, one sees the emergent power of the Lower Mississippi.

The MISSISSIPPI exhibition opened in Philadelphia at the University of Pennsylvania in September 1998 after which it traveled to several venues in the US and abroad. The book was published in 2001.

Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha made all the screen prints, drawings, photo-works, and paintings in the exhibition and book and hold copyright for the above.

Photo-credit for images of Mathur and da Cunha in screen-printing studio: Anne Whiston Spirn